If I were to ask you which direction New Zealand is located in relation to Australia, what would you say? Many people recall that New Zealand is to the north east of Australia.

This is incorrect. New Zealand is actually to the south east of Australia.

If you were one of the many who could have sworn that New Zealand was to the north east, you just experienced the Mandela effect. The Mandela effect is described as a ‘type of false memory that occurs when many different people incorrectly remember the same thing.’ It was coined by a self-described paranormal consultant named Fiona Broome, after she observed that many other people shared her memory of Nelson Mandela dying in jail in the 1980s when in reality he died in 2013. However, hundreds of people claim that they remember he died in the 1980s, several of whom are even able to ‘recall’ memories of his funeral being held.

Some more examples of the Mandela effect are as follows:

- The famous dialogue “Mirror, mirror on the wall” spoken by the queen in the opening of Snow White and the Seven Dwarves is actually “Magic mirror on the wall”

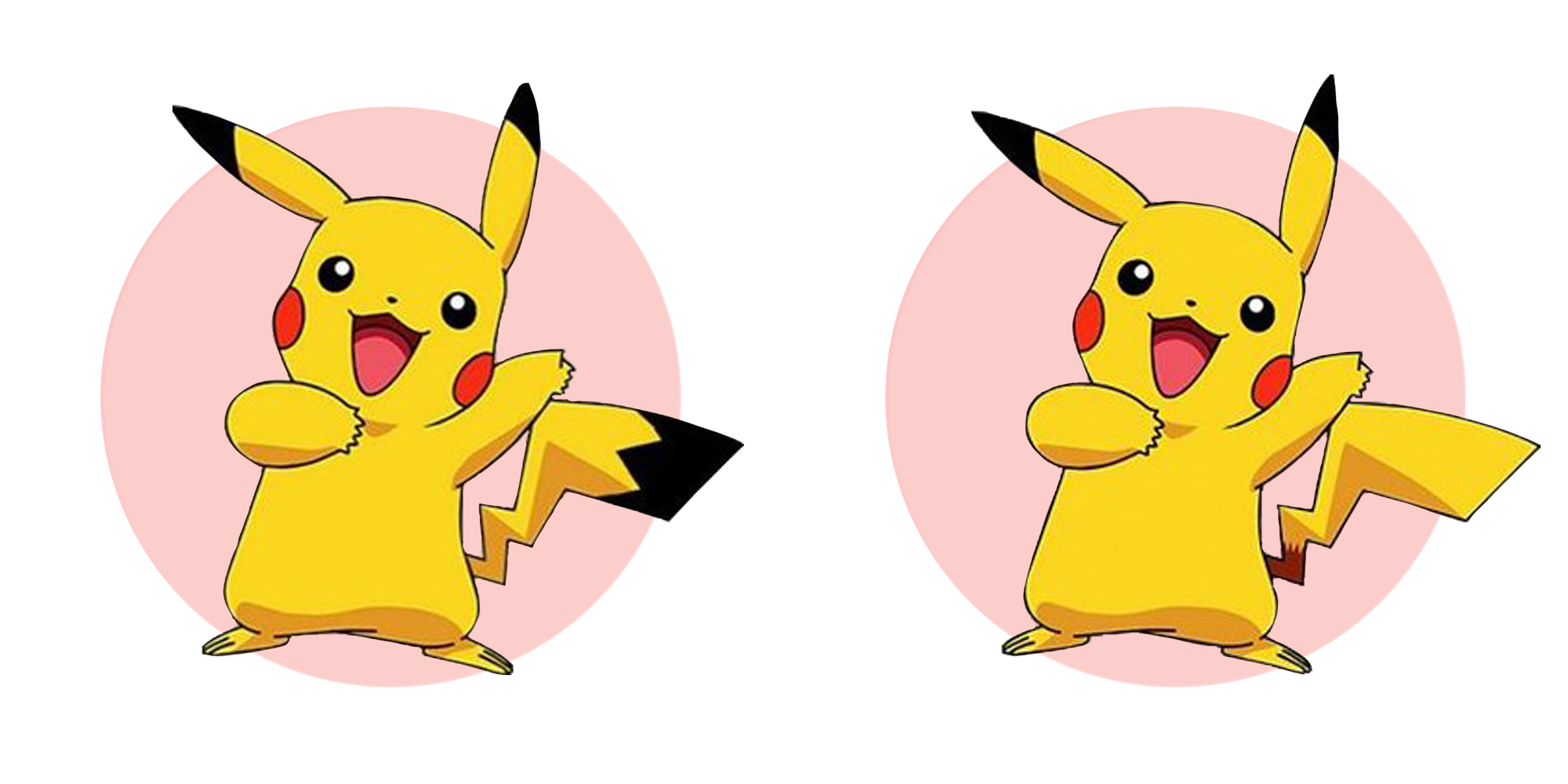

- The Pokémon character Pikachu is commonly remembered as having a yellow tail with black detailing, when in reality Pikachu’s tail is just yellow

- The monopoly man is commonly remembered as wearing a monocle, when in reality the monocle does not exist

In all of the above examples, a very large number of people remember the wrong thing. But how is it possible that so many people can share the exact same false memory?

Broome explains this phenomenon using the multiverse interpretation of quantum mechanics. As Encyclopedia Britannica explains,

“When not directly observed, electrons and other subatomic particles diffract like waves, only to behave like particles when a measurement is made. It’s as if these particles exist in multiple places simultaneously until directly observed.”

Schrödinger’s cat experiment was designed to explain this. Until one looks inside the box, the cat contained within theoretically exists simultaneously as dead and alive – once you look inside the box, the cat will definitively be only one of the two. However, some physicists such as the late Hugh Everett III, who was the first to propose the many worlds interpretation in 1957 speculated that both realities exist separately, in parallel universes.

This multiverse theory was created as an explanation for the results of physics experiments, but Broome draws from this to explain the Mandela effect; in her explanation, she and the others who remembered a different past regarding Mandela’s death were in a ‘parallel reality with a different timeline that somehow got crossed with our current one.’

Neuroscience looks at the Mandela effect a little differently, and believes it to be the result of three things:

- How our memories are stored and recalled

Our memory comprises of a network of neurons in the brain. Short term and long term memories are consolidated and stored differently. Now, when we recall a memory, that memory is reconsolidated – think of it as being reassembled from storage – and this process can sometimes cause a memory to lose its fidelity. Memories that are stored at the same time can also experience a sort of blurring of boundaries when reconsolidated.

An example of this was seen when Americans were asked to identify former US presidents in an experiment. In school, they were all taught that Hamilton was one of the founding fathers, but was never president. However, they were also taught about former presidents at the same time. Those memories were likely stored together, and gradually the memories of Hamilton and US presidents became so strongly linked that several adults in the study identified Hamilton as a former US president. This is an example of memory reconsolidation being distorted.

- Similar memories can overlap to create a new one

Another strong example of the Mandela effect is a film named Shazaam, created in the 1990s starring Sinbad as a genie, which several people remember well – a film that does not exist. There was, however, a film called Kazaam (1996) starring Shaquille O’Neal as a genie, and there were several other films that released around that time that had plot elements that overlapped with the descriptions provided of the non-existent Shazaam plot.

However, it is important to note that the people who described the Shazaam plot in detail as they ‘remembered’ it were not lying – they truly believed what they were saying. This is called confabulation, and it is a phenomenon wherein the brain fills in memory gaps with fabricated facts based on recognised patterns (which is why the Shazaam plot appears so believable, considering all the similar plots of films that were released around the same time).

- Suggestibility

Misinformation can dilute an original memory, and when this is replicated on a large scale, the new ‘meme’ can easily become the understood truth. Leading questions can also distort our memories. For example, the question, “Do you remember the 1990s film Shazaam starring Sinbad as a genie?” suggests not only that the film exists, but also creates a false memory of us having actually seen it.

The Mandela effect, though entertaining, ultimately reveals a rather unnerving truth: our memories cannot always be trusted.

Works Cited

Eske, Jamie. “What is the Mandela Effect?” Medical News Today. July 28th, 2022. Web. < https://www.medicalnewstoday.com/articles/mandela-effect > as seen on August 29th, 2022.

Liles, Maryn. “50 Mandela Effect Examples of Things You *Think* You Remember Correctly (That You've Actually Got All Wrong)” Parade. June 10th, 2022. Web. < https://parade.com/1054775/marynliles/mandela-effect-examples/ > as seen on August 29th, 2022.

Aamodt, Caitlin. "On shared false memories: what lies behind the Mandela effect". Encyclopedia Britannica, Invalid Date, https://www.britannica.com/story/on-shared-false-memories-what-lies-behind-the-mandela-effect . Accessed 29 August 2022.

Makes you wonder about a lot of things 😉